Growth is often constrained by operating capacity, not demand.

The signal usually does not show up in revenue or forecasts. It shows up when a missed trailer, delayed pickup, or failed handoff threatens to shut something down.

In conversations with CEOs, this often sounds like:

“Everything works until it doesn’t. And when it doesn’t, it’s never during a quiet week.”

As companies scale, the binding constraint often shifts from selling to executing. Volume increases, coordination becomes harder, variability expands, and operating models built for smaller scale begin to strain under edge cases. Throughput slows, management attention rises, and exposure to disruption increases.

Revenue may continue to grow, but execution becomes harder to sustain. The earliest signs rarely appear in dashboards. They surface first in day-to-day operations.

Early Indicators That Operations Are Constraining Growth

Operational drag rarely announces itself clearly. Instead, it shows up in patterns leaders recognize intuitively. As companies scale, change becomes calendar-bound rather than need-driven, with improvements deferred because certain months or volume levels feel too risky to touch. Execution reliability also begins to depend on a small number of carriers, lanes, or individuals whose performance is trusted but difficult to scale.

As volume rises, manual coordination persists. Core execution continues to rely on spreadsheets, email, and judgment calls, even as throughput increases. Flexibility is maintained through exceptions, with teams going outside standard processes or contracts as a necessary release valve rather than treating it as a failure of discipline.

In practice, this often looks like:

- leadership attention triggered by exposure rather than optimization

- senior involvement increasing only when execution threatens continuity

As one executive put it, “Inventories are getting tight… and if we don’t have a clear plan in place, our freight costs can get expensive. We’re entering January and February — our heaviest months — and typically making changes in those months is a challenge.”

Each of these signals is manageable on its own. Taken together, they indicate that the operating model is nearing its limits.

A Simple Internal Test

Leaders we speak with often use a few straightforward questions to understand where the real pressure sits.

Questions Leaders Ask When Growth Tightens

- Where would a missed shipment actually shut something down?

- Which people or relationships are holding the system together during spikes?

- What work would break first if volume increased meaningfully?

The answers are usually consistent across teams. The risk is already known. It just has not been named.

This is often where internal conversations stall. Operations teams feel the strain first. Leadership feels the risk last. Everyone agrees something is tightening, but no one wants to be responsible for introducing disruption.

What Effective Leaders Do Differently

Leaders who navigate this transition successfully focus less on fixing operations and more on reducing execution risk without breaking what already works.

1. Isolate Risk Before Optimizing Everything

The first step is not broad transformation. It is identifying where execution failure would most disrupt the business.

In most scaling organizations, this risk concentrates in a small number of flows:

- a subset of high-volume lanes, customers, or facilities

- peak periods with low tolerance for error

- workflows dependent on a few individuals or relationships

Rather than applying change everywhere, experienced leaders isolate these areas and treat them differently.

Why This Matters

Reducing exposure in a small, high-impact area delivers disproportionate risk reduction without forcing organization-wide change.

2. Test Change Through Pilots, Not Replacements

Leaders who have seen large implementations fail tend to reject rip-and-replace initiatives and for good reason.

More effective approaches frame improvement as controlled experimentation:

- starting with a limited number of shipments, orders, or workflows

- running new execution models alongside existing ones

- defining success in terms of reliability and continuity, not cost alone

Pilots replace debate with evidence. They allow leaders to observe performance under real operating conditions without committing the entire organization.

Why This Matters

Pilots preserve optionality. If performance improves, adoption can expand. If not, the business remains intact.

3. Separate Decision Authority From Execution Load

As scale increases, senior leaders often become informal backstops for execution risk. This can stabilize the system temporarily, but it creates dependency and distraction.

More scalable operating models distinguish between:

- decisions leaders retain, such as priorities, tradeoffs, and accountability

- execution work carried out day to day

In practice, this may involve moving execution work out of the core team, centralizing visibility, or relying on services that absorb day-to-day coordination.

The objective is not to remove control. It is to reduce how much executive attention is required to keep operations stable.

What to Look for Before Expanding Any Solution

Before scaling a new approach, experienced leaders look for specific signals.

Indicators That the Operating Model Is Ready to Scale

- fewer exceptions requiring escalation

- consistent performance during peak periods

- less reliance on individual heroics

- clearer ownership when issues arise

These indicators matter more than feature lists or promised efficiencies. They show whether the operating model can support growth without becoming more fragile.

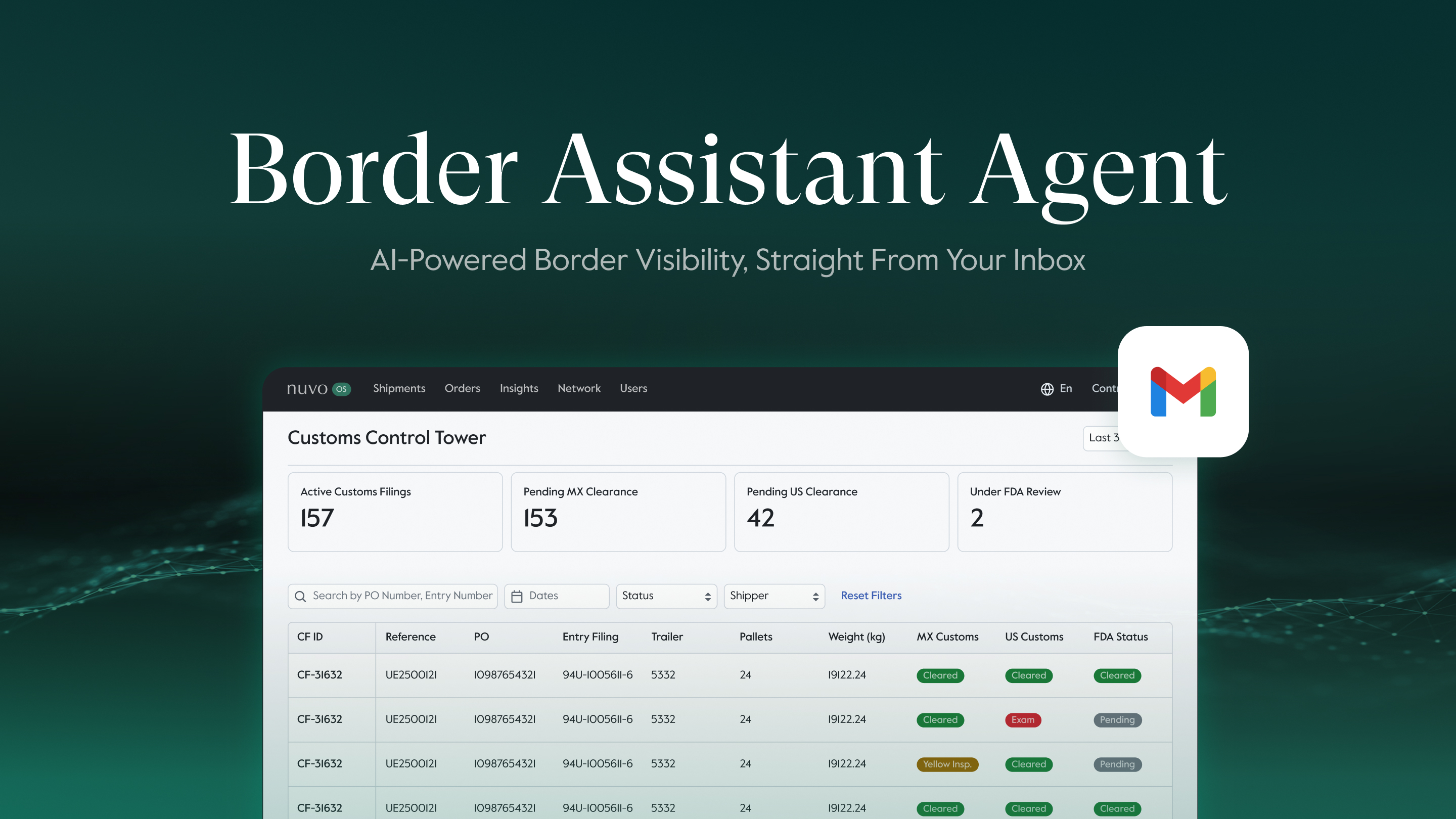

How Some Companies Are Handling Execution Differently

This is not a recommendation. It is an observation from companies under similar pressure.

In conversations with scaling supply chain leaders, a consistent pattern is emerging.

Execution as Infrastructure, Not Transformation

Rather than adding more internal tools, processes, or headcount, some companies are handling execution differently. They separate execution from system ownership while keeping decision-making internal.

This does not require replacing existing carriers, brokers, or internal systems.

In these models:

- execution is treated as infrastructure rather than a software rollout

- technology and automation are embedded into the service instead of implemented internally

- accountability for outcomes is explicit instead of spread across teams, tools, and vendors

Existing carriers, brokers, and internal processes typically remain in place. The execution layer operates alongside them, coordinating work, handling exceptions, and absorbing variability that would otherwise fall back on internal teams.

How Adoption Typically Starts

Adoption usually begins through limited, low-risk pilots:

- a small number of shipments, lanes, or workflows

- clear performance benchmarks focused on continuity and reliability

- full coexistence with current providers and processes

This allows leaders to observe execution performance under real operating conditions, including peak periods, without committing to a broader transition.

In most organizations, the hardest part is not execution itself. It is agreeing on where the risk sits when something goes wrong.

The appeal of this model is not transformation. It is risk containment. By externalizing execution complexity while retaining visibility and control, companies increase operating capacity without increasing internal coordination burden.

Final Perspective

Growth rarely stalls because companies stop selling. It slows when operating models built for one scale are asked to absorb another.

The leaders who navigate this transition successfully do not chase transformation. They isolate risk, protect continuity, and expand capacity carefully, using evidence rather than belief to guide change.

If this feels familiar, it is because many teams reach this point quietly, long before it shows up in results.